In 1992 he repealed section 2A of the Kenyan constitution and thus enabled nominal liberalisation of the media sector. They were vociferous critics of the administration and often uncovered stories about corruption and other scandals involving the ruling elite.īut Moi was forced into reintroducing political pluralism following economic and political turmoil, as well as international pressure. These were mainly newsletters, which appeared intermittently. This included a group of unprofessionally produced clandestine media, often with no known addresses. In addition, a range of alternative media sprang up. Kenyans found their voice through other institutions such as the church and civil society and in cultural spaces such as theatre and music. Their editors were either jailed, fined or forced into exile. This gave the government power to clamp down on the media in the interest of public morality, public order and national security.īetween 19 nearly 20 publications were banned. Although media freedom was provided for in section 79a of the constitution, it remained subject to the provisions of the penal code. Journalists and media organisations became particularly vulnerable to state intimidation. Critical journalists were intimidated and incarcerated. The government also began frustrating alternative news media. All government offices were required to buy copies of the Kenya Times. Through his ruling party, Kenya African National Union, he bought Hillary Ng’weno’s Nairobi Times and renamed it the Kenya Times.

He therefore set up a national party newspaper to act as a government mouthpiece alongside the state broadcaster, Kenya Broadcasting Corporation. īut Moi wanted total control of a news outlet.

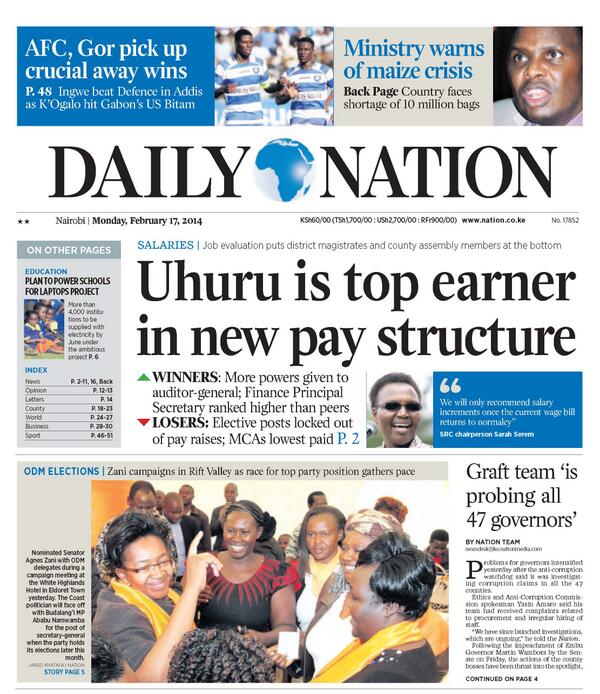

The government was, as it remains today, the single largest advertiser for the media. In the case of the East African Standard he became the majority shareholder through proxies.Īt the Daily Nation he exercised some control through his relationship with the proprietor as well as through the control of government advertising. This was a type of journalism that deliberately focused on positive “development” stories, especially those produced by the state.īut it was clear that the “nation-building” project was primarily a regime-building exercise, enforced through coercion and co-option.įor successful implementation, Moi’s administration found it imperative to control the dominant players in the media sector – the Daily Nation and the East African Standard. The idea of “development journalism” was part of the project. Many political leaders invented the project on the premise that it was necessary for national cohesion. The nation-building project was a popular development in the first post-independence republics across Africa. This process of political and state consolidation also involved the reinvention of what had ideologically sustained the Kenyatta state – the “nation-building” project. He had achieved near-total control of the country politically and constitutionally.ĭaniel arap Moi: the making of a Kenyan 'big man' And within three years – by 1982 – he had forced a constitutional amendment through parliament that saw Kenya become a one-party state. His aim was to break up potential centres of political competition. Once he was sworn in, Moi began a process of state consolidation. It was a messy succession and sections of the political elite weren’t comfortable. Moi (who died on 4 February 2020) became the president of Kenya in a constitutional succession following the death of the country’s first president, Jomo Kenyatta. His omnipresence was felt across newsrooms, all of which had his framed picture strategically placed to ensure journalists were aware he was watching them. He populated every public space like a fetish. Moi’s media persona was larger than the man. They were also told the colour of his suit and tie. Kenyans were told which church service he attended on the day. The Sunday broadcast news in the 1980s and 1990s was a familiar ritual of Moi’s diary. But no president has had a more terrifying presence in Kenyan newsrooms than Daniel arap Moi, Kenya’s president from 1978 to 2002. Kenya’s political leaders have always had a vested political interest in the control of the country’s media.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)